Almost anywhere you travel in Israel you can observe a wide variety of building styles, materials and construction techniques. These are all legacies remaining from the many different cultures which have passed through this region throughout the ages. Under Turkish rule of Palestine, non – Moslems were banned from purchasing land. This policy changed after the European support of the Turks against the Russians in the Crimean war, and after 1856 the ban was lifted, which led to intense building throughout the country, largely by the various European powers wanting to stake a claim in the Holy Land. In Jerusalem, it is easy to see how foreign intervention has made such an impact on the city. With its Russian Compound, German Colony, Italian Hospital and Austrian Hospice, to name but a few, we can tell how Israel’s capital became a magnet for different communities around the world who wanted a religious and political presence in the Middle East. As a result, the face of the capital was permanently altered and each of these master builders left an indelible imprint on the character of the city.

Of all the foreign powers that claimed a stake in the New Jerusalem of the nineteenth century, Germany did more building than any other country. An imperial visit played an important role in the development of the architectural landscape of Jerusalem and contemporary sources tell us that not only was the city changed forever by the German building projects, but that it was repaired and beautified in anticipation of the Kaiser’s visit.

If we start at the entrance to the Old City, the breach in the defenses by the Jaffa Gate was as a result of the large entourage that accompanied Kaiser Wilhelm and his wife Augusta Victoria on their sojourn to Jerusalem in 1898. The Turks very kindly agreed to blast a hole in the wall surrounding the Old City and fill in part of the defensive moat to enable them to make a grand entrance in their carriage which was too wide to fit through the gate. The purpose of their visit was to attend the corner stone ceremony of the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer in the Christian Quarter. This was an interesting architectural project as it incorporated the remains of a Crusader church built on the same spot many centuries earlier. Just so there should be no mistake as to who the current builders were, they integrated an eagle, the symbol of the German Reich into the façade. To make absolutely sure the German presence was seen by all, the church was designed to have the highest tower in the Old City.

As a result of this project, the Kaiser’s Catholic subjects in Jerusalem felt that the time was ripe to request a church of their own. This led to the construction of the Dormition Abbey on Mount Zion. This striking building modeled on the medieval Aachen Cathedral and built by the German architect Heinrich Renard, loudly advertises Germany’s presence, not least because of the church tower with its personification of the Kaiser with his helmet, eyes, nose and moustache.

An interesting footnote to this story is the claim that the land on which Dormition Abbey was built was originally owned by the Armenians and that the Turkish sultan forced them to sell it to the Germans. In revenge, they vowed that one day they would build a church higher than the abbey. In 1975 they began constructing the New Saviour’s Church in the Armenian compound next door, however, they ran into financial difficulties and construction halted in the 1990s. The scaffolding surrounding the incomplete structure is testament to their efforts.

Germany continued to have an impact on the urban skyline outside the Old City walls. The central one of the three towers on the horizon between Mount Scopus and the Mount of Olives is the Augusta Victoria Hostel, also built as a result of the imperial visit of 1898. A delegation representing all the German groups in Palestine visited the Kaiser and his wife and requested funds to set up a hostel to accommodate German pilgrims. Their petition was met with favour and the Empress who had admired the breathtaking view of the Old City from the Mount of Olives decided that was where the new project would be situated, it was also named after her. The Augusta Victoria compound was built in 1910 and included a sanatorium, in addition, a large church was built at the Kaiserin’s specific request. A condition of the Kaiser had been that the new building must resemble his ancestral castle at Hohenstaufen. He also insisted that the Mediterranean be visible from the west and the mountains of Moab to the east, so to that purpose a 60 metre high tower was built. Four large bells were also imported from Germany and brought up from Jaffa by special train. The Germans were determined that the bells in the Augusta Victoria tower should toll the loudest in Jerusalem.

During World War One this compound became the headquarters for the German and Turkish armies and during the Mandate period it served as the residence of the High Commissioner. He remained there until 1927 when the premises were damaged by an earthquake and he moved location to Armon HaNatziv, where the UN headquarters are located today. Augusta Victoria currently serves as a hostel, an Arab hospital and a church.

Another impressive building erected by the Germans during this period in the first decade of the twentieth century, is located opposite the Damascus Gate. At the time, the land on which the school stands was hugely sought after and it was only after outbidding both the Russians and the Jews that the Germans acquired ownership. With crenellations in its walls echoing those of the Old City ramparts facing it, the building is a fusion of European and Eastern styles. Designed by Heinrich Renard, the same architect that built the Dormition Abbey on Mount Zion, there are many similarities between the two projects. But by the time he planned this structure, Renard had obviously been influenced by regional architecture and departed from his strict adherence to European detail to include arches and domes, concepts which he must have seen in local design. Originally called the St. Paul’s Hospice, built to accommodate German Catholic pilgrims, today it is known as the Schmidt School. The present name commemorates the headmaster of a German Catholic school, originally located on Hillel street, where the Italian synagogue is today. The school moved to this location by Damascus Gate and currently functions as a girls’ school for Catholic Arabs. It is reputed to have one of the highest percentages of bagrut (matriculation) passes in the country.

Conrad Schick was a Swiss Protestant, who came to live in Jerusalem in the mid 1800s. Apart from his reputation as an architect (he designed several buildings in the city) and as a highly regarded researcher of Jerusalem, he was noted for creating a series of replica models of the Temple. They were held in such esteem that he was awarded a German knighthood in recognition of his work. Some of Schick’s models are on display in the basement of the school.

All of the above were constructed as a result of Wilhelm IIs visit and personal involvement, but German influence on the city does not stop there. In fact, preceding the emperor’s visit by around thirty years, a group of German Templers settled in Jerusalem. They were part of a new radical religious sect who believed they could set up the kingdom of G-d on earth and, in doing so, managed to get themselves ex-communicated from the Protestant church. The incentive for their move to Jerusalem was increased by an atmosphere of religious persecution and a distinct lack of funds. It wasn’t until the Kaiser’s visit to Jerusalem in 1898 that relations with Germany were repaired. The name “Templers” has nothing to do with the Knights Templar of Crusader times, but rather referred to their belief in a divine temple of the living. They wanted to hasten the coming of the Messiah by a synthesis of work combined with service to G-d, with its members leading an exemplary Christian life according to the principles of the Bible and the New Testament. Where else could we expect that community to live if not in the Holy Land, creating its centre in Jerusalem?

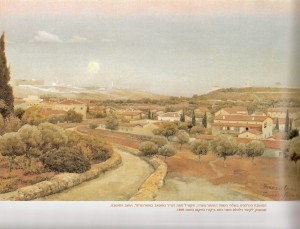

Actually, the first settlement was not in Jerusalem but in Haifa (where the German Colony still exists today), which served as an absorption point for those who followed them. The Templers established five colonies throughout the country: in Jaffa, in Sarona (today’s Kirya in Tel Aviv), Wilhelma (near Lod and today known as Bnei Atarot) and Bet Lehem of the Galilee between Haifa and Nazareth. The special quality of Jerusalem’s German Colony stems from its rural and village like atmosphere and in fact the layout mimicked that of a typical German street village. It includes narrow streets lined with red tile roofed houses, surrounded by low stone walls and pine trees. The facades of many houses in the German Colony still bear biblical inscriptions which express trust in the Lord’s help and provide encouragement. The remaining Templer neighbourhoods also preserve the rustic simplicity of the original founders.

The first generation of Templers were simple working class folk who actually provided assistance to the Jewish pioneers of the First Aliyah (1882-1903), teaching them farming methods and introducing them to European building techniques. However, they sent their children back to Germany to be educated and by the third generation they were imbued with the values of Hitler and the National Socialists. Hard as it is to believe, they held local Nazi parlour meetings and various items of Nazi paraphernalia including flags with swastikas and standards with SS emblems on them have been discovered in their former homes. With the outbreak of World War Two, the community was expelled by the British as enemy aliens and, for the most part, deported to Australia where many of their descendants still live today.

The slightly more modern Rehavia, is another neighbourhood whose appearance was influenced by German trends, albeit some decades later. Although it was created in the style of an English garden suburb during the time of the British Mandate, it was designed by the German Jewish architect Richard Kauffmann. Whilst Tel Aviv has received the UNESCO world heritage status of the “White City” because of its wonderful collection of Bauhaus buildings, Jerusalem can boast not a few of her own. Throughout the area, homes with clean, simple lines typical of the Bauhaus philosophy can be seen. In some cases this is fused with local architectural elements creating an “international style” deviating from the strict principles of functionality and form. A number of other Jewish German- born émigré architects also contributed to building in the area, such as Erich Mendelssohn who designed the windmill complex on Ramban Street, Yohanan (Eugene) Rattner who designed the Jewish Agency building and Fritz Kornberg who designed the Rehavia Gymnasium. Ironically many of the influx of German Jews (Yekkes) during the Fifth Aliya (1929-1939) settled in Rehavia where they contributed greatly to the city’s cultural, intellectual and culinary development.

Thanks for a very informative article!

Personally though, I think the Dormition Abbey tower on Mount Zion looks more like Homer Simpson…