A majority of tourists and locals have a good idea what they want to see when they go to Jerusalem’s Old City. Most of them don’t think twice about the fact that it is divided into sections or “quarters”. Today’s quarters only began to be called by their present names in the early nineteenth century. Residents of the city preferred to live amongst their own kind, but their populations were far from homogeneous, with Moslems living in the Jewish Quarter and vice versa. We are so used to visiting the “ancient Jewish quarter” or “ghetto” in cities all over the globe: Rome, Lisbon, Prague, Girona, Krakow, Marrakech, to name just a few, that it doesn’t seem strange that Jerusalem has one too. It should!

When King David conquered the ancient city of Jebus from the Canaanite tribe that lived here in approximately 1000 BCE and made it into the Jewish capital city, the people originally settled outside the current Old City walls. Whilst we have no exact figures regarding the population at this time, most archeologists and historians would guess around 1,000 individuals. Known today as “The City of David”, this early Jerusalem is bordered by the Kidron Valley to the east and the Hinnom Valley to the west. This is where the Jerusalem we read about in the Bible was situated and where prophets, kings and regular people walked freely. It was David’s son, Solomon, who built the Temple on Mount Moriah, to the north of the city, on land purchased by his father for fifty silver shekels from Araunah the Jebusite (see 2 Samuel 24:24). As the numbers of inhabitants in the city grew, particularly after refugees flooded Jerusalem as a result of the decimation of the north of the country by Assyrian forces in the 720’s BCE, they gravitated up the hill into the area of today’s Jewish Quarter. Over the ensuing years and centuries their homes and businesses expanded further to the north and west of David’s original capital and the Temple Mount. In 586 BCE Jerusalem was conquered and partially destroyed by the Babylonians. They enslaved the Jewish population and transported them to Babylon.

With a change of regime and permission given to the Jews to return to Jerusalem from their exile in Babylon, they started over again some 70 years later. They were guided by Nechemiah, who writes of his painstaking efforts to rebuild the city walls in a little-read account close to the end of the Bible, just before the book of Chronicles. Much later, during the Hasmonean dynasty (160’s BCE), the city once again increased in size. Under the rule of mega-builder King Herod, which started in 37 BCE, the Jewish capital was at its largest, only returning to similar dimensions in the 19th century! He undertook major building projects in the city and rebuilt the temple and greatly expanded the area surrounding it. During Herod’s reign hundreds of thousands of Jews lived in Jerusalem, with their numbers swelling to even greater proportions during the pilgrim festivals. Archeological remains dating from this time period in the vicinity of the Damascus Gate and the area of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, located in today’s Moslem and Christian Quarters respectively, give us some idea of Jerusalem’s dimensions. By the year 70 CE, just before its destruction by the Romans, Jerusalem’s northern wall (probably built by Herod’s successor, Agrippa) extended well into today’s modern city, a little south of the neighbourhood of Meah Shearim.

It was the Roman commander, Titus, who destroyed Jerusalem and Herod’s temple and expelled most of the Jewish population from the city. The final expulsion of Jerusalem’s Jewish inhabitants by the Romans took place under the emperor Hadrian, who erected Aelia Capitolina, a pagan Roman city dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva on Jerusalem’s ruins. After the Bar Kochba Revolt which ended in 135 CE, Jews were completely banned from entering Jerusalem and this edict was strictly enforced for several centuries (barring a one year blip between 362-3 CE under the brief reign of the emperor Julian).

It was the Roman commander, Titus, who destroyed Jerusalem and Herod’s temple and expelled most of the Jewish population from the city. The final expulsion of Jerusalem’s Jewish inhabitants by the Romans took place under the emperor Hadrian, who erected Aelia Capitolina, a pagan Roman city dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva on Jerusalem’s ruins. After the Bar Kochba Revolt which ended in 135 CE, Jews were completely banned from entering Jerusalem and this edict was strictly enforced for several centuries (barring a one year blip between 362-3 CE under the brief reign of the emperor Julian).

Only during the month of Av, when Jews mourn the destruction of both of their temples, were they permitted to visit the Foundation Stone on the Temple Mount. According to Jewish tradition, this is the place where Abraham bound Isaac and from which G-d took the earth that formed Adam and Eve. It was over this rock that the Holy of Holies was positioned, the innermost and most sacred part of the temple, where only the high priest was allowed to enter once a year on Yom Kippur. From the Roman period onwards, foreign rulers would dictate where Jews in Jerusalem were allowed to go. It set a precedent that was to have ramifications until the present day. This was the turning point. Jewish inhabitants of Jerusalem no longer had the luxury to decide where they wanted to live and would forever have their movements circumscribed by invading forces and external powers. Once the Romans adopted Christianity they were not any more charitable. There was no permanent Jewish presence in the capital at all under Christian rule and it was only with the Moslem conquest of Jerusalem in 638 that a limited number of 70 families were once more permitted to reside in the city. They were restricted to the area south of the Temple Mount, probably in the space known to us today as the Ophel.

The Dome of the Rock was built in 691 by the Ummayad ruler Caliph Abd-el Malik. It was not a mosque and the precise reason for its construction is still unclear and the subject of much speculation. One theory is that it was a victory monument for the Moslems who had inherited a beautiful city renowned for its stunning churches. As far as the Jews were concerned, it was a reincarnation of Solomon’s Temple and although the Temple Mount was to become a sacred place for Moslem prayer, they were allowed to assume janitorial roles sweeping it and cleaning and filling the glass lamps with oil. In–fighting between the various Moslem dynasties led to the  downfall of the Ummayads and the ascendance of the Abassids who were not nearly so tolerant of their Jewish subjects. Jews were now banned from entering the Temple Mount and had to console themselves by praying at its gates. By the 11th century and the rise of the Fatimid dynasty, conditions worsened and when the Crusaders conquered Jerusalem in July 1099, its Jews were massacred and those that managed to flee were banished from the city once more.

downfall of the Ummayads and the ascendance of the Abassids who were not nearly so tolerant of their Jewish subjects. Jews were now banned from entering the Temple Mount and had to console themselves by praying at its gates. By the 11th century and the rise of the Fatimid dynasty, conditions worsened and when the Crusaders conquered Jerusalem in July 1099, its Jews were massacred and those that managed to flee were banished from the city once more.

It was to be another eighty-eight years before they would be given permission to return. Jerusalem was conquered yet again and this time was at the mercy of the Moslem warrior Salah-al-din (aka Saladin). Jews were once again allowed to live in the city and many of those who took advantage of this leniency came from towns on the coast that had been destroyed by his Ayubbid army. They were later joined by North African Jews from Morocco and Yemen and European Jews from England and France. Their respite was short-lived, as the city briefly came under Crusader control again between 1229-1244, when the Jews were once more expelled. They were only allowed to return after 1260, when the Mamlukes, the next wave of Moslem rulers, assumed power.

Mamluke rule which continued for almost three hundred years saw the Jewish community built up from scratch, according to Rabbi Moses Ben Nachmanides, the Jewish doctor from Spain who arrived in Jerusalem in 1267 (known by his acronym as the Ramban). He wrote a letter home to his son, in which he lamented there were only two Jews in the whole city and he made it his mission to renew the Jewish presence in Jerusalem. He also established the tradition of Jews praying at the Western Wall. Until this time, Jews had prayed in different parts of the city dependent on where they were allowed access by the ruling power. During this era they could (with special permission) pray at the Western Wall, chosen by the Ramban as a site of prayer because it was now the closest place the Jewish population could get to the original Holy of Holies. According to an account written by Jacob of Verona, who visited the city in 1335, the community lived mainly in the area of Mount Zion. Other reports mention Jews living in caves in the Kidron Valley and eventually in homes in the present day Jewish Quarter. However, they were not allowed to enter the Temple Mount area.

The arrival of the Turks in 1517 initially heralded an upturn in Jewish fortunes, but after the death of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in 1566, onerous taxation caused them to leave the city in droves. The Jerusalem populace was devastatingly poor and unable to exist without support from Jewish communities overseas. When the Egyptians conquered Palestine in 1831 they introduced many reforms and for the first time since the Roman period, Jews were allowed to pray at the Western Wall without needing to apply for special permission. They were originally concentrated in the area of the Jewish Quarter, but quickly expanded north into the Moslem Quarter near the Temple Mount. The Jewish population grew from about 2,000 at the beginning of the 19th century to 45,000 at the end of the Ottoman period. In comparison, by 1917, on the eve of the British conquest, there were about 13,000 Christians and 12,000 Moslems. At this time Jewish families lived in the Bab Huta area (near the Flower Gate), in Hebron Street (opposite the area of the Cotton Market) and in the Street of the Steps, all in the Moslem Quarter. They built synagogues, yeshivas and other institutions such as a printing press and the offices of the Hebrew newspaper “Havatzelet” in the area. Jews also began to live in communities outside the Old City walls, starting with Mishkenot Sha’ananim in 1860. Some of the Yemenite community was housed in Kfar Shiloach in the ancient necropolis opposite the City of David, the biblical Jerusalem.

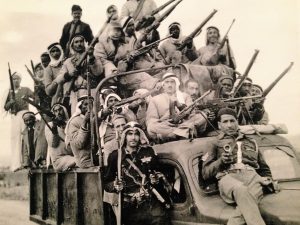

Under the British Mandate, Jews continued to live in the Old City in the Moslem and Jewish Quarters. However, Arab riots which started in 1920 on the eve of the San Remo Conference and continued throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s, eventually led to the Jews abandoning their homes as the assaults and killings escalated. Areas where Jews lived in the New City that bordered with Arab neighbourhoods were also abandoned, such as Meah Shearim and the Georgian quarter near Damascus Gate, as well as neighbourhoods in more outlying areas.

Arab riots which started in 1920 on the eve of the San Remo Conference and continued throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s, eventually led to the Jews abandoning their homes as the assaults and killings escalated. Areas where Jews lived in the New City that bordered with Arab neighbourhoods were also abandoned, such as Meah Shearim and the Georgian quarter near Damascus Gate, as well as neighbourhoods in more outlying areas.

Once the British formally withdrew and the War of Independence began in May 1948, the Old City was besieged by the most professional of the seven Arab armies that attacked the fledgling state, the Jordanians. They had been trained and equipped by the British, many of whom stayed on to help them attack. After a harrowing two weeks of house-to-house fighting, the Jews in the Old City surrendered on May 28th 1948 and its 1,300 remaining Jewish residents were once more expelled from their homes. 290 of them were taken prisoner by the Jordanians and the rest were moved to the New City. It would take another nineteen years until they could return as a result of the Israeli victory of the Six day War in 1967. Once again, they had to start building from scratch as the Jordanians had blown up most of the buildings in the Jewish Quarter.

The magnificent city of Jerusalem of old with its wondrous architecture and temple is mentioned in the fifth chapter of the Talmudic tractate of Sukka where it says: “He who has not seen Jerusalem in its beauty, has not seen a beautiful great city in his whole life; and who has not seen the building of the Second Temple, has not seen a handsome building in his life.” The post-1967 version tries to capture the essence of what once stood, but the ravages of time have played their role and the city which has been repeatedly and brutally dismantled by civilisations that have long ceased to exist, has itself almost disappeared. The Jewish Quarter of today is the smallest of the “quarters”, delineated in the present Old City walls, a sad footnote to its majestic and tumultuous past. The fact that Jews and non-Jews alike automatically assume they will visit the Western Wall during their stay in Jerusalem and the crowds that once more throng the streets during the festivals, are perhaps the greatest testament we have that Jewish Jerusalem has not been forgotten.

The magnificent city of Jerusalem of old with its wondrous architecture and temple is mentioned in the fifth chapter of the Talmudic tractate of Sukka where it says: “He who has not seen Jerusalem in its beauty, has not seen a beautiful great city in his whole life; and who has not seen the building of the Second Temple, has not seen a handsome building in his life.” The post-1967 version tries to capture the essence of what once stood, but the ravages of time have played their role and the city which has been repeatedly and brutally dismantled by civilisations that have long ceased to exist, has itself almost disappeared. The Jewish Quarter of today is the smallest of the “quarters”, delineated in the present Old City walls, a sad footnote to its majestic and tumultuous past. The fact that Jews and non-Jews alike automatically assume they will visit the Western Wall during their stay in Jerusalem and the crowds that once more throng the streets during the festivals, are perhaps the greatest testament we have that Jewish Jerusalem has not been forgotten.