Israel is full of archeological sites and often when we visit them it is very hard to remember that they were not originally as monochrome as we see them today, but in many cases were vibrant, colourful and highly decorated. In some places we have vestiges of frescoes that once appeared on the walls, but mostly the clearest hint we have of a building’s former beauty are the remnants of mosaic that still adorn the floors.

The art of mosaic evolved in the Greek world and was brought to this country for the first time during the Hellenistic period, which started in approximately 333 BCE with the arrival of Alexander the Great. During the Roman and Byzantine periods it developed and it became the main style of paving public buildings, private homes, bath houses, churches and synagogues. Most of the mosaics we have in the country date from the Roman or Byzantine era, but the fascination with mosaic art continues with many artists expressing themselves through this medium still today. By taking a good look at those little pieces of ancient coloured stone we can learn a lot about the communities that once lived here.

For a start, the size and quality of the tesserae can be compared to pixels. The smaller and better cut the stone, the more well defined the image and the costlier it was to produce. Larger tiles, fewer colours and less sophisticated workmanship indicate that the population did not have a huge amount of money to spend on creating their mosaic.

Different motifs give us an indication as to who lived in the local community. For example, in religious areas the mosaics do not generally depict people or animals and the tiles usually form geometric patterns. Often there is an inscription embedded in the mosaic which sheds light on specific donors or the period in which the mosaic was made. Even among non-representational artwork we can be in for a surprise, as in the case of the third century synagogue floor discovered in the ancient synagogue at Ein Gedi. It featured a black and white theme with a central focus that looked not dissimilar to the Nazi swastika.  This “meander” pattern has been found in several other sites throughout the country. Rather than indicating an early version of fascism, it was simply a popular shape used not only in our region, but also throughout the Far East. The floor is currently on display in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem.

This “meander” pattern has been found in several other sites throughout the country. Rather than indicating an early version of fascism, it was simply a popular shape used not only in our region, but also throughout the Far East. The floor is currently on display in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem.

A mosaic floor from a later period at the Ein Gedi synagogue includes the zodiac. In this particular example there are no pictures, each symbol is written out in words, once again testifying to the religious nature of the community. However, at the synagogues of Bet Alpha and Zippori, as well as several others, images of the zodiac feature prominently in their mosaics. How can it be that a pagan tradition was incorporated into synagogue decoration? It would appear that the work wa s commissioned at a time when the Jews were on good terms with the ruling regime and did not feel their religion threatened. The division of the months according to the zodiac is based on the movement of the sun, moon and stars. The Jews understood that G-d plays a central role in nature and is responsible for the heavenly constellations. They saw no contradiction in including the popular image in their design as it dovetailed nicely with their own beliefs.

s commissioned at a time when the Jews were on good terms with the ruling regime and did not feel their religion threatened. The division of the months according to the zodiac is based on the movement of the sun, moon and stars. The Jews understood that G-d plays a central role in nature and is responsible for the heavenly constellations. They saw no contradiction in including the popular image in their design as it dovetailed nicely with their own beliefs.

The major difference between Jewish and non-Jewish mosaics of the Roman period seems to be in their ultimate goal. We are fortunate to be left with some stunning examples from that time and in many cases their purpose seems merely to impress us with their beauty. This was very much in line with the building philosophy of the Romans and the Byzantines that followed them. What was most important to them was the façade and to create an atmosphere of grandeur and opulence. This is evidenced by the tall pillars and colonnades that usually surrounded the mosaics. The size, the splendour and the intricate patterns were all intended to induce the wow factor. Ferocious or exotic animals, beautiful women and mythical gods were popular themes.

Jewish art forms of the same period were less interested in ephemerals and more focused on content. If we look at synagogue art, the mosaic usually included a picture of the temple, religious items that were used in the temple like the incense shovel, or the four species used at Sukkot, or maybe a more universal Jewish symbol like the shofar. In addition, the scene of the binding of Isaac was often included in the tableau. These images indicated a yearning for the rebuilding of the temple and return to Jerusalem, a sense of tradition and Jewish unity. The inclusion of the biblical scene in which Abraham must face the ultimate test, shows how faith was at the very core of their beliefs. The illustrations conjure up memories of a period before the Temple was destroyed and remind the community of the times when G-d helped His people in the past and give them hope that He will help them again in the future. In this period the synagogue became a replacement for the temple, a “mikdash me’at” or “lesser temple” that would keep the existence of the Jewish people going until the real temple would be rebuilt.

We are fortunate to have discovered a number of mosaics from Samaritan synagogues as well. According to Samaritan beliefs they were the original inhabitants of Samaria who were not exiled with the Jews to Babylon. Other opinions suggest the Assyrians brought them to settle in Samaria when they conquered the land. Today they number around 700 and about half of them live in Kiryat Luza, close to their holy mountain of Gerizim, just outside Shechem and the others live in their community in Holon. They speak a special dialect, which is closer to Arabic than Hebrew and they have a different alphabet too. They celebrate only the seven festivals mentioned in the torah and do not keep Purim and Chanuka. Their new year is celebrated fourteen days before Pesach and the eve of Passover is marked by a sacrifice of lambs and goats on Har Gerizim. They are led by a high priest who claims to be descended from Aaron and they are divided into four clans: the priestly clan, and three other clans that descend from Joseph, Menashe and Ephraim. They also circumcise their sons on the eighth day.

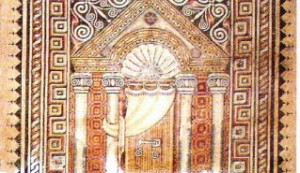

A recurring motif in their mosaic artwork is the temple façade, with its entrance covered by a curtain draped around one of the columns to allow a glimpse of the door. In addition, they depict images of items  used in their prayer rituals, such as silver trumpets and the produce of the land.

used in their prayer rituals, such as silver trumpets and the produce of the land.

Church mosaics also feature far less representational imagery and more geometric designs. In 2005, a mosaic was discovered inside Megiddo jail, which may yet prove to be one of the earliest church mosaics ever. One of several reasons archeologists make this claim is because the mosaic depicts a fish which was one of the first symbols of Christianity, long predating the cross.

The discovery of the mosaic is in itself an interesting story. Apparently the prison guards noticed the card games amongst the inmates had become somewhat more animated then usual. Upon closer observation they realized the players were competing for coloured chips. Gambling in prison, or playing for any prize is strictly against the rules and the wardens looked for the source of these tiles. It appeared the concrete floor of the recreation room was crumbling around the edges and the prisoners had found the coloured tiles lying around and used them to add a bit of spice to their card playing. When the concrete was removed, to everyone’s great surprise the mosaic floor was revealed.