When I was a young girl growing up in London, I used to belong to the Brownies, which was the junior version of the Girl Guides. One of our favourite chants was “Wanna Go on a Lion Hunt”? Our sing song took us through savanna terrain, and swamps in our pursuit of the king of the jungle. All this was acted out in pantomime accompanied by a specific set of actions and when we finally found our lion, we would hastily back track and do the whole charade in speedy reverse. A tourist to modern day Israel should not expect to come across a lion except if they are visiting a zoo, but the frequency with which lions were mentioned in the biblical text allows us to conjecture that lions and other wild animals were commonly sighted in ancient times. In trying to convince King Saul of his ability to fight the Philistine giant, David, the young shepherd boy assures the king he is used to dealing with wild beasts such as bears and lions who regularly come and attack his flock. Samson also struggled with a lion and lion imagery is so prevalent in the Old Testament that there are no less than six different Hebrew words used to describe the animal. The numerous references to lions, which appear in well over a hundred places, emphasise how often they were seen.

In many instances the bible describes the strength of the lion’s roar. It is likely that many more people had heard the lion than had stayed around to see it. That just made the prospect of coming face to face with one all the more frightening.

The prophet Amos who came from Tekoa in the Judean wilderness, correctly says “A lion has roared, who can but fear?” (Amos 3:8)

It is presumed the type of lion mentioned in the bible was the Asian lion which disappeared from Israel about 900 years ago. Today some of its descendants can be viewed in Jerusalem’s biblical zoo. However, whilst real lions may no longer roam the land freely, their likeness has become one of the symbols of the Jewish people. When the patriarch Jacob gave his death-bed blessings to his sons he referred to Judah as “a lion’s whelp…a lion, like the king of beasts” (Genesis 49:9). In so doing, he effectively created the symbol of the tribe of Judah, with which it, and later the Kingdom of Judah, would be forever associated.

Sometimes a lion appears not only to scare the people, but to deliver G-d’s message. In 1 Kings:13 there is a description where a “man of G-d” is sent from Judah to Bet El in order to denounce the new religion being established there by King Jereboam. The “man of G-d” is eventually killed by a lion because he disobeys G-d’s command. This lion is no ordinary predator, but is obviously on a divine mission as is suggested by his remarkable self control. He carries out his designated task to kill but neither eats nor mutilates the corpse, nor attacks the donkey who accompanied the victim. In a wonderful insight, Yael Ziegler posits that the lion not only represents divine will, but is also the symbol of the kingdom of Judah.

The noble qualities of the lion made it a mascot fit for a king and indeed the bible relates how King Solomon decorated the temple and his throne room with images of lions. A much later ruler, but one who is often associated with Solomon, is the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Legend tells us that the Turkish ruler was tormented in his sleep by a terrifying vision of four lions devouring him. The next morning he called all his interpreters to him and requested an explanation of his macabre dream. Nobody was able to come up with an answer until an elderly courtier asked the sultan what he had been thinking about before he went to sleep. He answered that he had been contemplating how to punish those citizens of Jerusalem who did not pay their (already harsh) taxes. The interpreter told him that Jerusalem was a holy city and a special favourite of G-d/Allah who protected it against those who would do evil there and the lions had been sent to destroy him. In order to reverse the decree Suleiman needed to atone for his wicked intentions. So the Sultan set out to visit the city and found it desolate and in ruins. He decided to rebuild walls around the city and he ordered two pairs of lions like the ones in his dream to be positioned over one of the gates. These were to serve as a warning for generations to come and as a symbol of how Allah had changed the Sultan’s heart from carrying out a cruel decree to restoring the city and rescuing it from its ignominy. This is how the Lion’s Gate received its name. There are those purists who quibble that the lions are not really lions but rather leopards or panthers and that they were part of the heraldic symbol of the Mamluk leader Baybars…but that is another story.

Jerusalem has been the capital of the territory of Judah since the time of King David and in 1950 the ubiquitous lion became the emblem of the modern city. I invite you to come on a modern day lion hunt with me and see if you can identify where these lions illustrating the blog are located. Answers are below.

Lion #1 in front of a private house in Talbieh’s Marcus Street is part of a series of 80 lions that was created in 2002. It was the brainchild of artist Aliza Olmert wife of then mayor, Ehud Olmert, who had seen similar projects in other parts of the world. The basic unadorned, sculpted lion was given to a variety of artists to decorate. They were later auctioned off with the proceeds going to finance different programmes to benefit the children of Jerusalem.

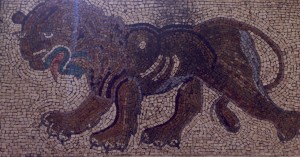

Lion #2 is part of a mosaic in the Yad ben Zvi Institute in Rehavia. It is actually a copy of a mosaic floor from the ancient synagogue of Ma’on in the Negev, near today’s Kibbutz Nirim. The original mosaic dates back to Byzantine times when it was common to find such artwork in a synagogue. Two lions flanked a menorah which itself had feet shaped like lion’s paws. During this period when the temple was no longer standing, the synagogue was considered as a “mikdash me’at” or lesser temple, a substitute for what once had been. Much of synagogue art depicted Jewish symbols that reminded the people of better times and tried to encapsulate the essence of their faith.

Lion #3 is a stone statue in the courtyard of the Soldiers Hostel in Jerusalem near Sacher Park. It was sculpted by David Ozeransky, who was born in the Ukraine and came to Palestine in 1929. He studied at the Bezalel School of art. He is also the creator of a far better-known lion sculpture in the city: the winged lion that sits atop the Generali Building on Jaffa Road.

Lion #4 is located just a few feet away at the entrance to the Yad LeBanim soldiers’ memorial complex. According to creator Sam Philippe, his bronze sculpture of a lion standing at over 9 feet tall and weighing approximately a ton, is one of the largest in existence. Considering that his debut into the world of art was making sculptures from chocolate he has come a long way. Today his (smaller) sculptures have been presented to leaders around the world as gifts from the Israeli government.

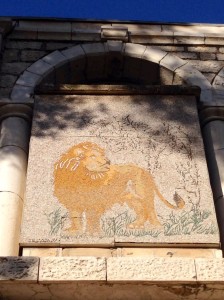

Lion #5 is another mosaic, this time above the entrance to the Natural History Museum in the city’s German Colony. The museum building was originally built by an Armenian businessman in the 19th century. It later became the home of the Turkish governor, then the British High Commissioner and still later became an officer’s club. The Natural History Museum was established in 1962 and is dedicated to local wildlife and fauna. It has an eclectic range of exhibits including a stuffed lion and lioness presented to the city by none other than Idi Amin from the days when he was Governor of Uganda.

If you have a snapshot of your favourite Jerusalem lion, send it to me and I will put up a collection on my facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Helen-Cohn-Israel-Tour-Guide/462609387192220