Over the last few years Israel seems to have developed an obsession with trains. Whilst the train system in the north of the country is pretty efficient, in many other areas, especially Jerusalem, it certainly leaves something to be desired. Metropolitan Jerusalem now boasts its own “Light Rail” system which is really a glorified tram, but in those few neighbourhoods where it operates it does seem to do the job quite well. So much so, that Tel Aviv appears set to follow suit. However, the big news will be when the capital city is finally connected to Tel Aviv by a high speed train where the journey will take only half an hour…but we’ve got a while to wait before that happens, although work is already underway constructing the line. Like many projects these days it is both way over budget and behind schedule, but the most unbelievable story so far about the proposed new link was when it was recently discovered that two of the tunnels (the longest in Israel) were being built in the wrong place!

In the meantime, you can take a very scenic ride along the original route that first connected the two cities in 1892, but don’t expect to get there in any hurry, as it takes close to an hour and a half! The windy track which runs along the Sorek riverbed was designed to interfere as little as possible with the natural water sources along the way. For that reason the first trains went over no fewer than one hundred and seventy six bridges. The original five stops on the line were also chosen because they were close to an accessible supply of water. Today, however, it doesn’t matter in which direction you are travelling, when you reach the terminus you will be able to visit the original city station which has been renovated and gentrified to create a very nice cultural and commercial hub. Both “The Tahana” in Tel Aviv, which was the original Jaffa station and “The First Station” in Jerusalem, had a virtually identical design. They have both been restored and are once again thronging with people.

For those travelers on the original route, the journey between the two cities would have taken close to six hours and that was assuming there were no unforeseen delays! Still, that was half the time it had taken previously by horse and carriage. Several well-known personalities rode the railway including Theodor Herzl, the German Kaiser Wilhelm ll, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel and Israel’s first prime minister David ben Gurion, to name but a few. When they reached the end of their journey they would have been welcomed by jostling crowds and a cacophone of noise as they made their way along the station platform. Local residents came to welcome the train and hawkers and beggars would vie for the passengers’ attention and money as they walked past. In harsh winters when there was heavy snow, travelling by train was the only way to enter or leave Jerusalem.

For those travelers on the original route, the journey between the two cities would have taken close to six hours and that was assuming there were no unforeseen delays! Still, that was half the time it had taken previously by horse and carriage. Several well-known personalities rode the railway including Theodor Herzl, the German Kaiser Wilhelm ll, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel and Israel’s first prime minister David ben Gurion, to name but a few. When they reached the end of their journey they would have been welcomed by jostling crowds and a cacophone of noise as they made their way along the station platform. Local residents came to welcome the train and hawkers and beggars would vie for the passengers’ attention and money as they walked past. In harsh winters when there was heavy snow, travelling by train was the only way to enter or leave Jerusalem.

Another important train route that ran through Palestine was built in the early 1900’s during the Ottoman era and was called the Hejaz Railway. The Turkish sultan’s original idea was to construct a railway that would run from Damascus to Mecca to serve the Moslem pilgrims who were embarking on the Haj. A special mosque carriage with a minaret two and a half metres in height was added to the train especially for their use. The tracks eventually only made it as far as Medina due to the outbreak of World War One, much to the relief of the local Bedouin tribes who had a very profitable business ferrying the pilgrims between the two cities.

Several branch lines were added including one that ran from Haifa to Dera, on the Syrian border, where it met up with the main line to Medina. This section was called the Jezreel Valley Train and included stations at or close to Acre, Bet She’an, Afula and Tiberias. The proximity of the railway led to the development of these areas which had previously been very isolated. It also helped promote the region as a place for tourists to visit. In a recent government initiative, sixty kilometres of this historic track is to be renewed in order to connect the centre of the country with the periphery. Trains running at one hundred and sixty kilometres per hour are due to start operating on this line in the summer of 2016. The old stations in Kfar Yehoshua and Afula have already been renovated and the cornerstone laid for the new Bet She’an station.

During World War One, the British managed to gain control of the Valley railway and by World War Two there were six daily trains travelling along this route. During the period after the Second World War when relations between the Jews and British soured, the Jewish Resistance Movement, which was an amalgamation of all the various resistance groups, bombed the Valley line near Afula station. In 1946, as part of an operation called “The Night of the Bridges,” whose aim was to immobilise the British army, the Palmach blew up one of the main bridges on the line and as a result the Jezreel Valley line was completely cut off from the rest of the Hejaz railway. Further bombing raids carried out during Israel’s War of Independence crippled the line even further.

Another branch line, this time to the South of the country, was initiated by the Turks during World War One. Be’er Sheva station opened in October 1915.The current mayor of Be’er Sheva decided it would be a good idea to renovate his city’s Turkish era train station too, and in the spirit of nostalgia he also wanted an authentic train to sit in it. Initially used for freight trains only, a passenger service from the station was inaugurated in 1956 with a freight train created for the British Palestine Railways. They eventually sold it to the Israel Trains Authority and for eighteen years it was used to transport Be’er Sheva residents to Haifa. Many of them still remember its distinctive whistle. Eventually it was superseded by a diesel engine which did the job much more efficiently and the original train was sent to a scrap yard.

As similar trains were still in use in Turkey until as recently as thirty years ago, the mayor entered negotiations to buy one from there. However the strained relationship between Israel and Turkey was a deal breaker. Not willing to give up his search so easily, the mayor discovered that train enthusiasts in England had already purchased a steam locomotive from the Turks just like the one that was used in Be’er Sheva. Their goal was to ensure it was preserved for posterity. The Brits were prepared to sell their engine for a not inconsiderable sum, on condition the Israelis didn’t let Turkey know they were selling the train to Israel, so as not to cause a diplomatic incident. In the end the mayor’s tenacity paid off and earlier this year the train was shipped to Israel from England and proudly installed in its new home in Be’er Sheva.

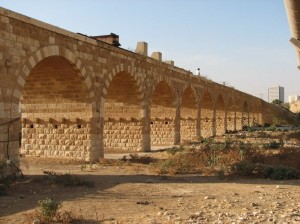

It was the Zionist visionary, Theodor Herzl, who first posited the idea of a suspension railway in Palestine in his 1902 utopian work “Altneuland”. We haven’t quite got there yet, but every so often as you are travelling around Israel you will be able to catch a glimpse of one of the bridges used by these long defunct lines. They stand as testimony to the entrepreneurial spirit that has become a hallmark of the country and an affirmation of Herzl’s dictum “If you will it, it is no dream”.