July has arrived and with it the Hebrew month of Av. Traditionally thought of as a gloomy period because the first nine days are spent in mourning recalling the destruction of two temples, culminating with a 25 hour fast, I think it has got an unfairly bad press! Just a few days later on the 15th of the month we celebrate the traditional grape harvest with a festival of love. The rest of the month is spent enjoying the summer, often going from festivity to festivity as wedding season is in high gear.

This contrast between joy and sadness is one of the fixtures of the Jewish calendar and maybe the secret to the longevity of the Jewish people. Our history is chequered with highs and lows, with destruction and rebirth. Perhaps our understanding that even when it looks like all the chips are down there is still hope, is what has ensured our survival. Ironically, even though life in Israel is rigidly compartmentalized, with everyone placed squarely in a particular box, it is precisely that ability to think out of the box, not to be beaten by circumstances, but to come up with original ideas, which makes Israeli innovations such a success in the modern world.

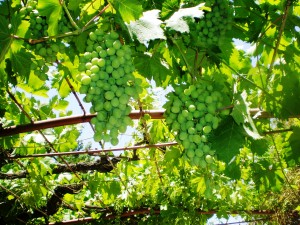

One of the industries in which we had a head start on most of the rest of the world was wine making. Wine has been part of our tradition from the very earliest biblical episodes. The first reference we have to wine in the Bible is in the ninth chapter of Genesis, which relates the story of Noah planting a vineyard after he came out from the ark and getting drunk. In a later event, in the book of Numbers, the scouts who came on a pilot trip to the Promised Land return to Moses and their fellow Israelites with a huge cluster of grapes, so big that it needs to be carried by two people. Neither of those two incidents had a great outcome. Nevertheless after a somewhat rocky introduction to the fruit of the vine, it became a vital part of life here in ancient Israel.

According to Deuteronomy, chapter 20, any man planting a new vineyard was exempt from military service and in the book of Isaiah there are clear instructions given how to plant said vineyard. A different prophet, Micha, even paints an idyllic scenario of every man sitting under his vine and fig tree. The Kings of Judah owned vast areas of vineyards and King David employed two officials to manage them. Kings Solomon and Herod built temples financed by international trade and winemaking in ancient Israel was at its peak in the Second Temple Period. It was a major export and the economic mainstay of the area. Grapes and vines were also frequent motifs on coins and a symbol of the fertility of the country.

Inscriptions and seals found by archeologists in Israel indicate that wine was traded in Ashkelon, Dor and Jaffa, the port areas of the country. Pottery and ancient seals have also been found in England dating from Roman times, belonging to wine sent from here. Every church and many synagogues had mosaics depicting grapes, harvests and wine related scenes. Hundreds of wine presses have been found throughout the country. Wine from the Holy Land was a brand name product!

So what happened? How did we end up with the reputation that Israeli (read kosher) wine was to be avoided at all costs? That sickly sweet pungent liquid produced by Israeli wineries was to be used for religious ceremonies only and even then you shouldn’t drink too much of it unless you wanted a hangover! From a world leader in the industry how did we fall so low?

Unfortunately, none of the ancient varieties of grape that were used in this country from biblical times onwards survived, because they were uprooted after the Moslem invasion. The vineyards were not immediately attacked because actually there is no explicit ban in the Koran against drinking wine. Various warnings are issued about the dangers of drinking, but that is as far as the text goes. In fact, according to some, Mohammed himself is said to have drunk wine, although there are some differences between commentators in this matter. There are those who say his drink was indeed made from grape juice and others who say it came from apples, presumably some kind of cider. Regardless of what refreshment the Moslem prophet originally drank, as Islam became more and more extreme, wine was outlawed. Although Jews and Christians could make and drink it they were not allowed to sell it to Moslems.

When the Crusaders were in charge there was a brief respite and even an increase in local wine production, but once the land came under Moslem control again this waned. The Mamlukes, who conquered the country in 1291, were the most extreme of the Moslem rulers and they decreed anyone who drank wine would be hung. They burnt all the vineyards and that is why none of the ancient varieties of grapes for producing wine are still in existence.

Nevertheless, wine remained deeply rooted in the Jewish psyche and, in the 1800’s, when the Jews managed to gain concessions from the Turks after the Crimean War, a few home wineries, started up. There were said to be over twenty wineries in the Old City of Jerusalem alone. They relied on varieties of grapes intended for eating, which are different from those used for making wine, but that was all they had. However, the industry was really given a new lease of life at the end of the nineteenth century, during the time of the First Aliya, with the investment of Baron Rothschild in the Carmel Wineries. He spent a great deal of money importing new strains of grapes from Europe in order for the local wine industry to develop. Even so, the winemakers did not have the expertise of their forebears and the wine they produced was Kiddush or sacramental wine, known in Hebrew as “yayin patishim” (hammer wine) for its not so subtle qualities and it was a far cry from the superior Chateau Lafitte produced by the baron’s French vineyards.

Nevertheless, wine remained deeply rooted in the Jewish psyche and, in the 1800’s, when the Jews managed to gain concessions from the Turks after the Crimean War, a few home wineries, started up. There were said to be over twenty wineries in the Old City of Jerusalem alone. They relied on varieties of grapes intended for eating, which are different from those used for making wine, but that was all they had. However, the industry was really given a new lease of life at the end of the nineteenth century, during the time of the First Aliya, with the investment of Baron Rothschild in the Carmel Wineries. He spent a great deal of money importing new strains of grapes from Europe in order for the local wine industry to develop. Even so, the winemakers did not have the expertise of their forebears and the wine they produced was Kiddush or sacramental wine, known in Hebrew as “yayin patishim” (hammer wine) for its not so subtle qualities and it was a far cry from the superior Chateau Lafitte produced by the baron’s French vineyards.

In the 1970’s, a visiting US professor of wine, from Davis University in California, remarked that the Golan Heights looked like the perfect terrain on which to plant vines. A few enterprising kibbutzim took him up on the idea which led to the formation of the Golan Heights Winery in 1983. They are credited with revolutionizing the Israeli wine industry and seriously upgrading the quality of Israeli wine. They brought over American wine expert Peter Stern to work for them. As well as being chosen for his expertise, he was picked for his Jewish sounding name. Even though he turned out not to be Jewish, he stayed on as their wine advisor for the next 20 years!

Today there are over 200 wineries in Israel ranging in size from the big five (Carmel, Barkan, Golan Heights, Binyamina and Tepperberg) who each produce over one million bottles a year. Then come the medium size and boutique wineries and the smaller “garagistes”. They are included in the boutique category and in many cases literally operate out of garages or other home facilities. Israeli wine is collecting prizes in international competitions and slowly moving off the “kosher wine” shelves and inaugurating an awareness of “Israeli wine”, as consumers begin to appreciate the quality and variety of wines Israel now has to offer.

Israeli technique is a fusion between the two styles of wine making known as “Old World” and “New World” and as a result is coming up with some very impressive wines. “Old World”, primarily refers to wines made in Europe, but can also include other regions of the Mediterranean basin with long histories of winemaking such as North Africa and the Near East. The phrase is often used in contrast to “New World” wine which refers primarily to wines from New World wine regions such as the United States, Australia, South America and South Africa.

Old World wine making is influenced by tradition and terroir, with the emphasis on how well the wine communicates the sense of place where it originated. Terroir, is the terrain or growing habitat where the grapes are grown and can be affected by soil composition, altitude, wind, temperature, climate change and a host of other details. Old World winemakers pride themselves on largely determining the quality and taste of the wine as a result of their work whilst the grapes are still on the vine and have yet to be harvested.

New World winemakers are not so constrained in their ideas and are more open to experimenting with scientific advances and initiate more involvement during the fermentation stage. Using strains of cultured yeast or enzymes to influence the flavor of the wine are just two of the methods they may consider. Israel is very much a mix of old and new world techniques. On the one hand we have the tradition going back over 2000 years, on the other, we are not frightened to combine this with the latest developments. If the medals we are collecting at international wine tastings are any indication, it seems to be a winning combination.