With the festivals of Passover and Easter overlapping this year, large numbers of day trippers hit the roads all looking for the ultimate day out. In an attempt to avoid the crowds, yet still travel somewhere with relevance for the holiday, Hubby and I took ourselves off the usual tourist trail to the shores of the River Jordan.

Qasr el Yahud is known to Christians as the site of Jesus’ baptism and subsequent epiphany and is marketed primarily towards the Christian pilgrims that visit the country. Less well known, is that it is also considered the spot where Joshua is said to have crossed the Jordan River with the Israelites and entered the Promised Land. Given that the festival of Passover commemorates the Israelites exodus from Egypt and their deliverance by G-d, this seemed an eminently suitable spot to contemplate these events. The day on which Joshua crossed the river with the children of Israel in tow was five days before they celebrated the Passover festival. What a wonderfully fitting end to the exodus saga when, after forty years of wandering in the desert, the Jewish people finally get to celebrate their deliverance in their new homeland.

The miracle of the parting of the Red Sea is familiar to most people, but the fact that another similar miracle took place here, when the Israelites crossed the River Jordan, is less well remembered. The flow of water coming towards the people from upstream was stopped and “piled up in a single heap” (Joshua 3:16) and the waters which were flowing downstream from them dried out completely, enabling the people to cross over on dry land.The verse continues: “So the people crossed near Jericho” (Joshua 3:16). The entrance to Qasr el Yahud is directly opposite the city of Jericho. We read that Joshua and the Israelites went there shortly after their arrival in the land, after their initial encampment at Gilgal.

The miracle of the parting of the Red Sea is familiar to most people, but the fact that another similar miracle took place here, when the Israelites crossed the River Jordan, is less well remembered. The flow of water coming towards the people from upstream was stopped and “piled up in a single heap” (Joshua 3:16) and the waters which were flowing downstream from them dried out completely, enabling the people to cross over on dry land.The verse continues: “So the people crossed near Jericho” (Joshua 3:16). The entrance to Qasr el Yahud is directly opposite the city of Jericho. We read that Joshua and the Israelites went there shortly after their arrival in the land, after their initial encampment at Gilgal.

Until a couple of years ago, Qasr el Yahud was inaccessible without prior co-ordination with the army. Throughout the 1970s this was a place where infiltrators made their way into the country from Jordan. As a result, the Israeli army enclosed the area and scattered land mines to deter terrorists. Over the years, requests were made by many of the local churches to come to the site and conduct religious ceremonies at Epiphany and Easter. These applications became more numerous, until even Pope John Paul II held a private prayer service here in the year 2000, during his official visit to Israel. This event only increased the sacredness of the place for Christians and the Israeli authorities decided to clear some of the mines in order to allow access to the site. You are still sternly warned not to stray from the clearly marked paths.

Heavy flooding in 2003 set back renovations that had already begun, as the pavilion that had been erected was swept away. But an investment of seven million shekels by the Ministry of Tourism has ensured the opening of the area to tourists and provided the necessary facilities for their comfort. Various churches at the site testify to the importance of the place for Christian worshipers.

The day of our visit was Easter Sunday and a mass was in full progress. In addition, there were several people immersing themselves in the rather murky water. As you can see from the photo, the River Jordan is very narrow at this point and it would have been a desirable spot for the Israelites to cross over from the eastern shore.

Another biblical episode is also reputed to have taken place at this location and that is the taking up of Elijah the prophet to heaven. He and his successor Elisha stood on the banks of the Jordan and, yet again, the waters parted when Elijah struck the water with his cloak. As they crossed, a fiery chariot and horses appeared and took Elijah heavenwards in a whirlwind, leaving Elisha alone.

One of the explanations for the Arabic name of the place is that “Qasr” comes from the Arabic word “break” and the name was given because this is the spot where the Jews “broke” the waters. In any event, it is definitely worth a short visit to soak up the atmosphere (pun intended) and ponder on the events attributed to have taken place in these tranquil surroundings.

A fifteen minute drive away, one and a half kilometers off the main road that connects Jerusalem to the Dead Sea, is another site that has a somewhat different association with the holiday.  The seven day festival of Passover recalls the story of the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt. Moses is the dominant player in this drama (although his name is not mentioned in the traditional recitation of the story as it appears in the Haggada), but after forty years of leading his unruly charges in the desert, he is ultimately denied the opportunity to enter the Promised Land and has to content himself with a far off glimpse. Jewish and Christian tradition place Moses’ lookout on Mount Nebo in Jordan, across from Jericho and the Dead Sea. Having seen the land his ancestors are to inherit he dies and his grave is unmarked and the exact location unknown.

The seven day festival of Passover recalls the story of the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt. Moses is the dominant player in this drama (although his name is not mentioned in the traditional recitation of the story as it appears in the Haggada), but after forty years of leading his unruly charges in the desert, he is ultimately denied the opportunity to enter the Promised Land and has to content himself with a far off glimpse. Jewish and Christian tradition place Moses’ lookout on Mount Nebo in Jordan, across from Jericho and the Dead Sea. Having seen the land his ancestors are to inherit he dies and his grave is unmarked and the exact location unknown.

A Moslem tradition dating to the days of Saladin, introduces a seven day festival where the participants march from Jerusalem to Jericho from where they can look over to Mount Nebo and the tomb of Moses. Nebi Musa (meaning “Prophet Moses”) was built as a hostel on the way, from where the celebrants could also look over towards Moses’ final resting place.

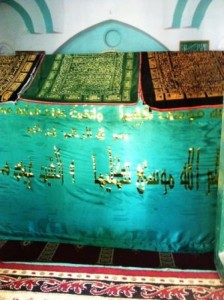

Under the Mamlukes and their leader, the Sultan Baybars, a small shrine was added to the site, as part of a general policy they carried out when conquering towns and rural areas. Usually, they are better known for their scorched earth policy all over the country, where they reduced existing structures to ruins. These shrines were mostly dedicated to biblical prophets and the one in Nebi Musa was no exception, dedicated to the Prophet Moses.

Over the years the hostel to accommodate the travelers was expanded to one hundred and twenty rooms. With time, the initial purpose of the site became blurred and rather than being a lookout to a distant burial place, the area became confused with the site of Moses’ actual tomb.

Around 1820, renovations to the rooms were once more carried out. This time by the Ottoman Turks, who also initiated a national and religious pageant to the tomb, in order to compete with the large number of Christian pilgrims who came to Jerusalemfor the Easter holiday. This new tradition with an agenda soon became a symbol for Moslem religious and political power. Thousands of Moslems would gather in Jerusalem for the trek to Nebi Musa. Their expenses were footed by the Moslem religious authorities and wealthy Moslem Jerusalemite families. On the seventh day, the pilgrims would make a triumphant return to Jerusalem. By the early twentieth century an estimated 15,000 people participated in the pageant.

In 1920, the pilgrimage took a distinctly sinister turn, degenerating into riots and attacks on the Jewish population of Jerusalem. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 and its assurance of a national homeland for the Jews, combined with Arab disappointment regarding promises of independence they claimed they had been given during World War One, led to this nationalist attack. Goaded by inflammatory political speeches and Arab and Moslem agitation from outside the country, what was ostensibly a religious parade turned into a pogrom. Six Jews and four Arabs were killed, over two hundred Jews were wounded, large amounts of Jewish property were burnt or pillaged and torah scrolls desecrated. In what would be an uncanny foreshadowing of the events of Kristallnacht which would take place in Nazi Germany eighteen years later, the Jews were blamed for the riot. A significant decision implemented by the British as a result of the violence was that legal Jewish immigration to Palestine was halted. This was a major demand of the local Arab community.

The processions to Nebi Musa were finally outlawed by the Jordanians when they conquered the area in 1948. The event had become a vehicle for political protest, something the Jordanians had no desire to encourage.Since 1995, as a result of the agreements of the Oslo Accords, Nebi Musa has been under the control of the Palestinian Authority.

When you visit the site today, none of the turmoil of the past is evident. It is a sleepy structure with a few Bedouin selling drinks and trinkets near the entrance. The locals are friendly towards visitors and are happy to answer their questions. There is none of the usual tourist infrastructure or even explanatory signs, but for those looking for something a little off the beaten track, it makes for an interesting detour. If you are lucky, like we were, you may even come across a herd of wild camels grazing peacefully in the stunning desert landscape.